UK Medical Practice: Why are doctors leaving?

30 Nov 2021 | Anne Marie Fogarty

| Share with

Five different health organisations in the UK, namely the General Medical Council, Health Education England, The Department of Health (Northern Ireland), NHS Education for Scotland, and Health Education and Improvement Wales, were all involved in recent research ‘Completing the Picture Survey’ – to analyse ex-UK doctors who have left the UK market and if they would reconsider moving back.

- The inclusion criteria were doctors who had practised in the UK for more than three months but less than 15 years.

- The research involved 13,158 doctors and was completed online.

- Most doctors who had left the UK practice, be it due to retirement, movement to another country or any other factor, were reluctant to return and practice in the UK.

- The main objective of this research was to analyse why they left, their willingness to come back, and anything that can motivate this willingness.

What were the key reasons for leaving?

First, the report aimed to help understand the critical demographic traits of doctors who stopped working in the UK. The survey was subdivided to include the doctor’s role before leaving, when they left and their gender. Most of the doctors who left were specialists with 32%, while the least were trainees with 21%. According to gender, most leavers were males with 57.7%, while only 42.3% of females left. There was a notable high influx of doctors with a disability who left with 10.1% left compared to 5.9% registered. Brexit has affected the choice of doctors leaving their practice in the UK, with 23.9% of EEA primary medical qualifications leaving. Demographically, doctors with a disability, male doctors, and EEA PMQ doctors tended to leave their UK practice within the last fifteen years.

The research also related to motivational issues which might have influenced the movement of the doctors. All the 13,158 doctors were given different reasons to choose from to indicate why they decided to leave the UK, and one would give at least five reasons in numerical order. The reasons ranged from:

- Working environment

- Retirement

- Personal reasons like family, financial, disability, health.

The results indicated that most doctors moved due to reasons associated with their working environment. The dissatisfaction with work or their role was the primary reason taking 35.72% while 32.04% returned to their home country. Bullying, harassment, and mental health issues also played a part in this decision-making process, although in small bits.

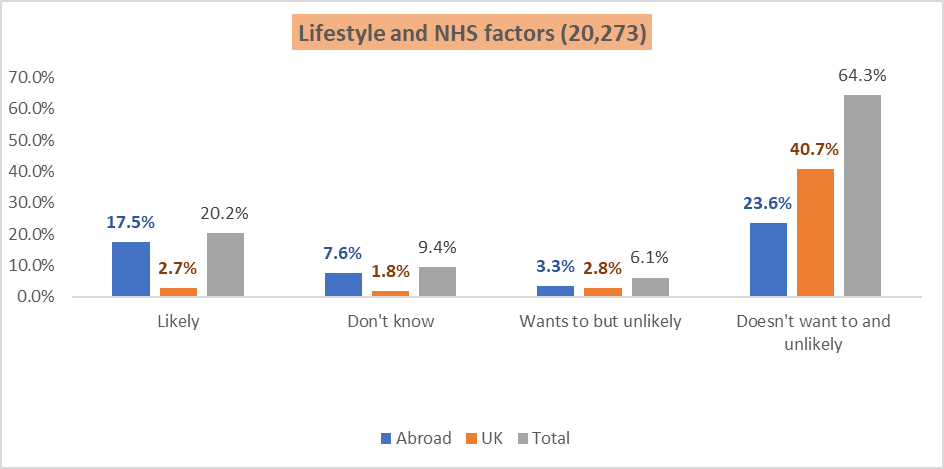

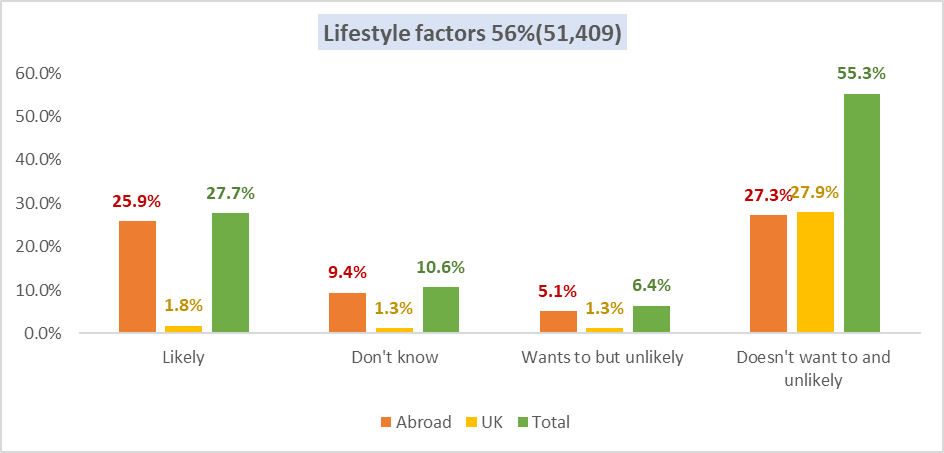

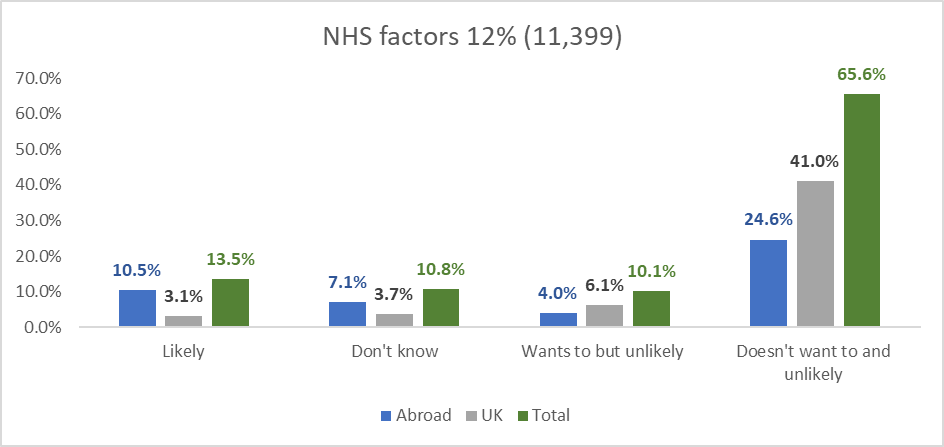

The data were also analysed by dividing the reasons into two broad categories of NHS and lifestyle factors. NHS factors related to the working environment and culture determined how the doctors were treated in their roles. Lifestyle factors included reasons such as retirement, family, and other personal responsibilities. From the results attained, 56% of the doctors moved due to lifestyle and family issues, while only 12% moved due to unconducive working environments. Different roles in the medical practice carry different responsibilities; thus, the positions of the doctors also played a part in their moving. For example, GPs had more work and experienced burnout compared to specialists.

Figure 1: Lifestyle and NHS factors 22% (20,2730)

Several motivation factors also affected the doctor’s decision to move, which differ from one doctor to another.

Figure 2: Lifestyle Factors 56% (51,409)

Figure 3: NHS factors 12% (11,399)

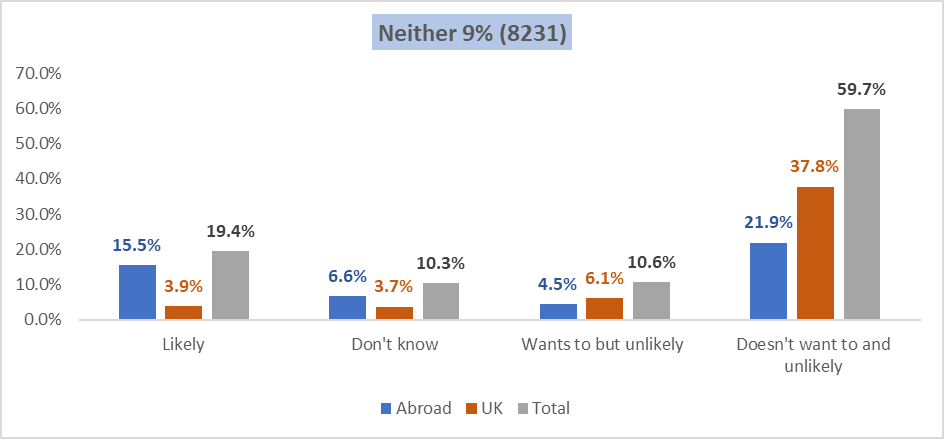

Figure 4: Neither Lifestyle nor NHS Factors 9% (8231)

Analyses of the whole population of doctors – 91,313 doctors.

What is the likelihood they will return to the UK?

After identifying why they left, it was critical to understand how many doctors would be willing to return and practice in the UK again.

Likelihood to return

13,158 doctors completed the online survey (discussed at the beginning of this article) from an identified population of 91,313. Below we now will analyse the whole population of 91,313 doctors.

Figure 5 and 6 below shows the relationship between willingness to and the likelihood of return. It highlights a large concentration of doctors who don’t want to return and are unlikely to do so, alongside a smaller but still significant group who want to and are likely. But there are also doctors whose position seems more ambiguous, e.g., those who wish to return but are unsure and some who don’t want to return but are likely to do so.

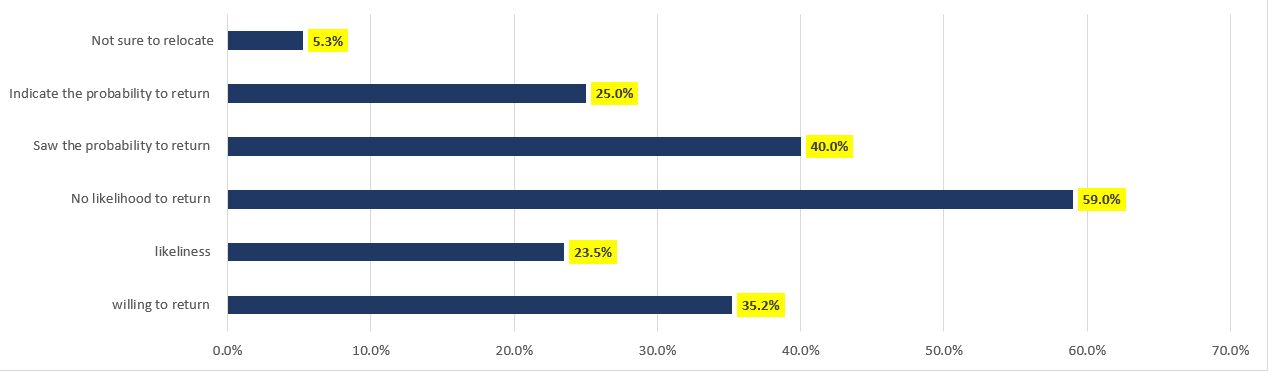

Figure 5: Illustration of the likelihood of doctors to return

From the whole population of 91,313 doctors, 35.2% were willing to return, while only 23.5% indicated the likeliness of that happening. The data showed that most doctors had no desire to return and saw no likelihood of the same, at least 59% of the doctors, while 40% saw a probability of returning, with 24% indicating the probability of the same. For those willing to return, over 4,800 of them were not sure of their relocation area in the UK where they would be willing to settle. The timeframe since they practised in the UK also affected their tendency to return.

The research also compared the specialty that those willing to return would play. It indicated high similarity between those who left and those showing a likelihood of returning. Most of those unwilling to return were retired doctors, with only 6% of those who had retired showing the desire to return. It was mainly related to their retirement status and weakly associated with their age.

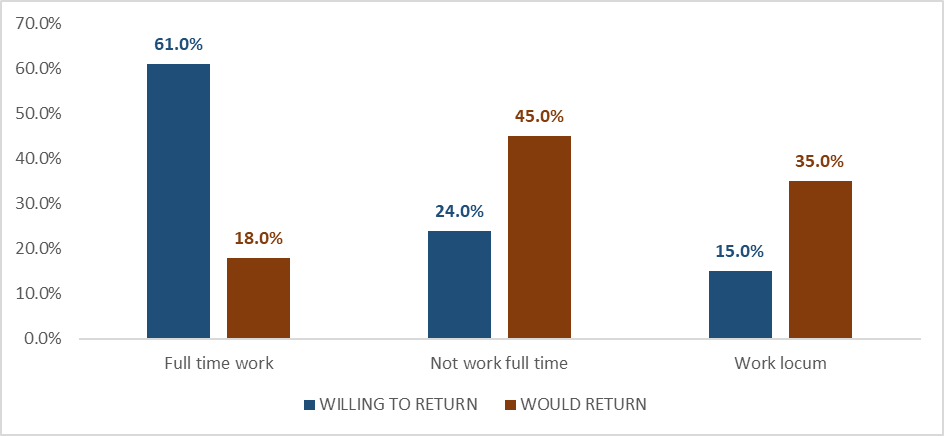

Figure 6: Willing to return and to what position the doctors would practice in.

Another factor to consider for those willing to return was the hours they were willing to work. Initially, 61% of the doctors in the population worked full time, 24% did not work full time, and 15% worked locum. For those who would return, 18% said they would work locum, 45% full time while 35% less full time. It indicates that those willing to work full time had reduced significantly. Therefore, it’s notable that over ten times of doctors were willing to return from abroad, but those who initially worked as GPs were not willing to return to the same positions. These numbers are clear indicators if not call outs for a more flexible approach to the working week. It is evident from the research that doctors abroad would prefer to return to flexible working arrangements rather than full-time schedules. So how can we support this as a nation wanting its’ doctors back? Through investment in collaboration between the flexible workforce and the Government and NHS, we believe, based on the evidence, that we would then be answering the doctor’s demand, therefore, attracting them back to the UK and supporting their retention here.

There are several barriers and enablers which affect doctors return to practice in the UK. Getting this data from the population would require an analysis of the roles played by the doctors currently wherever they are and if the same reasons which caused their moving are still holding them from returning. Over half of the doctors (56.1%) work clinically abroad, 29.6% are retired, and the rest work in clinical and non-clinical conditions. This data indicates that most doctors moved due to working conditions as they still work in other locations. The doctors were then asked to indicate why they were not returning to the UK, which gave similar results as to the reasons for their moving. Most opt to remain in their place of residence as they are happy there, while negative reasons for not returning revolved around job security, induction, and worry about their skills.

Migration issues, including visa and regulations, jump out evidently as reasons for not returning. The UK has a strict revalidation process for medical personnel, which might be a high cause of this reasoning. The primary reasons for leaving, which had been burnout and job dissatisfaction, had faded away and did not indicate high causes of not returning. For those doctors who indicated lifestyle factors as their cause of leaving, their likelihood of return was higher than those who left because of their work environment.

So, we looked at a sample (13,158) of the doctors at the start of this article to see their reasons for leaving the UK. Then looked at the whole population (91,313) to see what the likelihood of their return to the UK was. Now, lastly, we look at an additional piece of research that was conducted on a sample of 63,280 doctors who indicated their willingness to return to the UK. It was meant to analyse what effect a formalised return program would have in motivating them to return. 83.5%, a high number of the doctors indicated they would be willing to return if the industry introduced a formal return program. Such a program would be preferably specialised to the individual needs of the doctors. However, the doctors would consider the real-world impact of the program in such cases to know the program’s effectiveness.

Migration and diversity

The Anglophone countries have a high attraction rate to doctors leading to their migration to these countries such as Australia, the USA, and New Zealand. Data indicates that the migration rate of doctors is very high compared to those migrating into the UK, with most of them going to work clinically abroad, with most of them having a UK PMQ. Visa issues, as indicated above, were also shown to affect most doctors who are willing to return to the UK but cannot – something that perhaps, at a government level, could access change?

It was impossible to conduct this research without analysing equality, diversity, and inclusion. As indicated, most doctors leaving the UK were males whose influence was more on financial reasons, and the same applied to their barriers to return. Doctors with disabilities indicated that bullying, mental illness, and burnout caused their departure, and they were afraid to return on the same basis. As for specialty, IMG doctors reported visa issues as their barrier to returning, while EEA PMQ indicated the likelihood to return to their country of residence instead of the UK.

How can we support the return of and retention of our doctors?

So, we know who is leaving, why they are leaving and what might attract them back from the survey.

The research is robust and evident of a real need to attract, train, and retain our wonderful doctors to the UK. Investment in better working conditions, staffing solutions and less stress in the workplace are essential if we are to stock the UK with quality doctors for the future.

Working hours and conditions scored high in the research as reasons for leaving the UK. Suggesting a better work-life balance, better staffing solutions, and lighter workloads are essential for wellbeing and retention. Our doctors want a better quality of work while also balancing their professions. Flexible workforce strategies allow for that quality of life, that balance of personal and professional while supporting the whole healthcare system within the UK.

A word from our CEO

As CEO of a successful flexible workforce solution organisation, ProMedical, my team and I continue to witness first-hand from talking with thousands of healthcare professionals on the ground that the above survey is a clear illustration of the present landscape in the UK.

Doctors are leaving for many reasons, such as:

Retirement, better life-work balance, less stress, less working hours, better work environment, easy access to other countries (visa regulations etc.), and overall better quality of life. But we can provide that same quality of life here in the UK, if not better. If we take on-board this research, listen to the doctors, and hear their stories. There is nothing impossible in the study – nothing we in the UK cannot actually provide. We can attract more doctors here, by easing visa regulations, or at minimum providing more clarity on the regulations, by an attractive returns package, we can provide a better work-life balance with more flexible workforce solutions, we can relieve stress by better wellbeing and mental health policy development and audit, and we can retain our doctors by ensuring they are listened to, provided for and work with flexibility and a good life-work balance.

At ProMedical, we are committed to challenging the status quo. We have a professional, ethical, and social responsibility to all our customers, healthcare colleagues and ultimately patients. We are all aware of the old idiom ‘To rob Peter to pay Paul’. Well, I believe, it is time to reimagine this story where our role becomes a ‘safety-net’ to the NHS in order to retain the severe talent fallout we continue to witness. This, in turn, prevents Pete from being robbed and also protects our NHS from a patch-job; we know current workforce challenges are anything but a quick-fix.

We reached out to industry leaders for their expert opinion.

Mr Suhail Mirza, Chairman, NED, & specialist advisor to the healthcare and recruitment sectors | Qualified Life Coach | Speaker | Writer. On reading our piece, Mr. Mirza commented,

“With record rising demand for services, significant skills shortages and a healthcare workforce under continued operational and emotional pressure, the UK can ill afford to lose doctors from the system.

This article illuminates the varied reasons that doctors are leaving the UK (largely to work culture and mental health challenges) and rightly calls for intervention from policymakers to reverse this worrying trend.

I agree with the wise and passionate call from Altin Biba on all of us who partner with the NHS and social care system to play our part not only to advocate for policy change but to ensure through our actions that we support the inclusion and wellbeing of all our doctors.”

Mr Neil Carberry, Chief Executive Officer at Recruitment & Employment Confederation, comments,

“These findings on the medical workforce align with a wider trend we are seeing across the UK labour market right now. Staff are selecting roles on purpose – which has rarely been an issue for doctors – but also on conditions. Trusts need to think about how staff are deployed, their facilities, flexibility and how they are treated. Relying on purpose alone is not enough – doctors have choices. Getting the right balance of substantive and locum staff managed well will be at the heart of success in our health system in years to come. Government will need to make sure they focus on value and sustainability, not just price. Also, look to future supply – both domestic training and the attractiveness of the UK as a destination for those coming to work.”

We approached more experts for their welcome thoughts on the essence of why our doctors were leaving the UK and what we can do collaboratively to attract them back, following the recent research findings. The consensus appears to be a deep reflection is required at a top tier planning level across the UK. Investment and collaboration between government, service providers and policymakers to ensure retention of our medical resources. Our NHS provides one of the best services in the world but needs the government’s backing to make sure they have qualified doctors at hand to deliver the service safely and sustainably.

Conclusion

The research indicated diversity in the medical profession through the many reasons cited by different doctors regarding their departure and likelihood to return to the UK. Many doctors are moving from the UK medical practice and moving to work clinically abroad. Most doctors who did not want to return were retired, which is understandable as they are done with their careers. The doctors gave the reasons to shed light on what the government and the medical industry in the UK can do to encourage doctors to remain practising in the UK and attract those working abroad.

As a solution-focused organisation, we are confident that with government investment and amendment at the policymaker level, that we, in collaboration with our NHS, can attract and retain medical talent back to the UK.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

30 Nov 2021 | Leave a comment

Share with socials